This case study is presented as a phenomenological account of first-person embodied experiences of Peter Zumthor’s 2011 Serpentine Pavilion in London. This account was first written in 2011 as a direct experience and revisited as a remembered experience, darwing on the power of mental images.

Frances Downing (1994, cited in Malnar and Vodvarka, 2004, p. 22) helps bring precision to the principles defining mental images:

Mental images are an active, vital repository of information gathered through sensual experience – through sight, sound, smell, touch and taste. […] [A mental image] does not include all the environmental information contained in a particular place or event experience. Instead, the mental image presents a version of experience that is most important to the individual or situation at a particular moment in time.

Zumthor is known for his striking integration of sensory qualities in the design of his buildings (Ursprung 2014) and I had the opportunity to visit his London Serpentine Pavilion twice. The first time the weather was bright and relatively sunny while the second time, it was raining abundantly. The weather is mentioned here because it had a significant impact on sensory variability in the pavilion due to its design. According to Kellert (2008) sensory variability, the level of variation in sensory phenomena such as light, sound, touch and smell in an environment, impacts on human satisfaction and wellbeing and as such, can impact on people’s ability to develop intimate connections with their surroundings.

In the first instance, my experience of the corridor as I entered the building was especially powerful. Inside, intimate proportions, the modulated light, the mellow darkness and relative quietness provided a welcome refuge from the vastness and brightness of Hyde Park as well as the noise of traffic nearby. Robinson (2015, p. 57) highlights the significance of surface materials in Zumthor’s pavilion design. She explains how he seduced visitors by coating the burlap walls in black paste to introduce texture and micro-shadows to deepen the darkness of the interior (Figure 1). She doesn’t write about the smell but through my own experience, I know that a faint but comforting smell emanated from the walls. Upon entering the corridor, my body attuned to its environment, ‘[t]here was no need to hurry, no urge to move on’ (2014, p. 39). I felt an embodied connection with the environment. Zumthor had designed the outside of the pavilion as a simple black rectangular box hiding the inside so the experience was serendipitous. By including an opportunity for an unexpected phenomenon with special qualities to occur, Zumthor created a significant and memorable experience whose image still resonates with me today.

The corridor entirely surrounded the interior and the thresholds, from the outside into the corridor and from the corridor into the core of the interior, were cleverly staggered. This design feature protected the intimacy of the interior by providing a refuge from the more chaotic reality of the outside world. Covatta (2017) equates this form of intimacy to mental wellness and the interior, a simple cloister-like space with a rectangular garden of wild flowers as a central focal point, did present a peaceful and restful outlook. The experience was pleasant. The edges of the space were lined with benches integrated into the architecture, as well as tables and chairs inviting people to pause. Tuan (1977, p. 138) identifies pause as one of the conditions necessary for individuals to experience a sense of place. He writes that ‘[p]lace is a pause in movement. Animals, including human beings, pause at a locality because it satisfies certain biological needs. The pause makes it possible for a locality to become a centre of felt values.’ The ability to pause can thus be an opportunity for individuals to attune to their surroundings.

Beyond the biological need to rest, people tend to prefer secure and protected settings (Kellert et al. 2008, p. 13) and the recessed sitting area nested against the wall and protected by a short overhanging roof presented a nested opportunity for private positions from which to enjoy the garden. Bachelard (1958) relates the nest to the concept of inhabiting, linking the ability to withdraw into one’s intimate territory to pleasure, while Nakamura (2010) adds sensory precision to the concept of pleasure by explaining that, due to their intimate size, nests minimise distances and maximise opportunities for bodily contact with space through an active relationship between the structure of the space and the body.

Aside from its role as a natural focal point, the variety of plants, their colours and complexity of details contrasted with the simplicity of the architectural forms and materiality. This complexity also contrasted with the view to the sky above. Although the design of the pavilion eliminated all connections to the outside and people could seek protection under the overhanging roof, the garden remained open to the sky with the top of the trees in the park still visible. This feature provided a distinctive and enticing, even poetic, mental connection to the outside.

The edges of the space were busy, occupied by people, adults and children sitting on the furniture provided, some chatting, some eating, a few people reading, some simply resting while others strolled around the garden. All seemingly relaxed and enjoying the space (Figure 2). Following the more contemplative experience of the corridor I began to attune to the more convivial mood of the garden. Mallgrave (2015, p. 6) explains that the recently discovered mirror mechanism underpins human empathy and is the reason why we can easily share emotions with others. As such, the sight of people relaxing can have a positive effect on the mood of others as it did on mine.

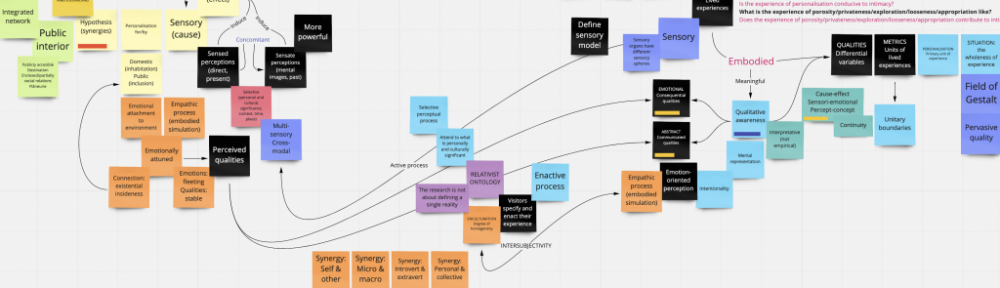

During the second visit, the interior of the pavilion was almost empty and thus quieter because it was raining. While previously people dominated the experience of the space, this time I became immersed into the experience of the Summer rain falling onto the garden through the open roof, watching, listening to, touching and even smelling its humidity. Drops of water fell heavily onto the edges of the metal tables, creating a rhythmic sound pattern and visual liquid explosions (Figure 3). Even though it was raining, the overhanging roof offered protection and the experience was comfortable and relaxing. With little disruption, my mood was contemplative. During the previous visit, my body had attuned to the environment in the corridor however, while previously it felt like a sudden unexpected force, this time it occurred more gradually, as if my body was slowly easing into the atmosphere of the space. I tried to capture these experiences in a phenomenological map (Figure 4).

Even though the pavilion was temporary its design as a refuge, the choice of materials, the garden, the visual connection to the park and the thoughtful integration of natural elements, grounded the interior and gave it a natural relational presence. It felt authentic. Interior designer Mary-Anne Beecher (2008) expresses a link between authenticity and atmosphere. She argues that for a place to cultivate atmosphere, the setting requires an authentic and meaningful contextual grounding. Moreover, despite knowing that it was a temporary space, the environment also exuded continuity, projecting a temporal connection between past, present and future. Till (2013: 95) refers to it as ‘thick time’, when ‘[in] its connectedness, time places architecture in a dynamic continuity, aware of the past, projecting into the future.’ In this instance, a sense of continuity emerged from the surface materials such as the worn patina of the burlap walls and aged timber whose slight imperfections could be imagined as a reference to past occupancy, while the cloister like design also seemed to reference a historical architectural context. Although the black box of the exterior felt incongruous in Hyde Park, once inside, it felt that the interior had always been there.

Bibliography

Bachelard, G. (1958) The Poetics of Space. Boston: Beacon Press.

Beecher, M. A. (2008) ‘Regionalism and the Room of John Yeon’s Watzek House.’, Interior Atmospheres. Architectural Design., pp. 54-59.

Covatta, A. (2017) ‘Density and Intimacy in Public Space. A case study of Jimbocho, Tokyo’s book town.’, Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health, 3(5).

Downing, F. (1994) ‘Memory and the Making of Places’, in Franck, K.A. & Schneekloth, L.H. (eds.) Ordering Space: Types in architecture and Design. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, pp. 233-235.

Kellert, S. R., Heerwagen, J. H. and Mador, M. L. (eds.) (2008) Biophilic Design. The Theory, Science, and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

Mallgrave, H. F. (2015) Architecture and Empathy. Espoo, Finland: Tapio Wikkala-Rut Bryk Foundation.

Malnar J. M., Vodvarka K. (2004) Sensory Design, Minneapolis, Minn.: University of Minnesota Press.

Nakamura, H. (2010) Microscopic Designing Methodology. Tokyo: Japan: INAX Publishing.

Robinson, S. (2015) ‘Boundaries of Skin: John Dewey, Didier Anzieu and Architectural Possibility’, in Tidwell, P. (ed.) Architecture and Empathy. Espoo, Finland: Tapio Wirkkala-Rut Bryk Foundation.

Till, J. (2013) Architecture Depends. Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England: The MIT Press.

Tuan, Y. F. (1977) Space and Place. The Perspective of Experience. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press.

Ursprung, P. (2014) ‘Presence: The Light Touch of Architecture.’, in Wilson, V. & Neville, T. (eds.) Sensing Spaces: Architecture Reimagined. London: royal Academy of Arts.